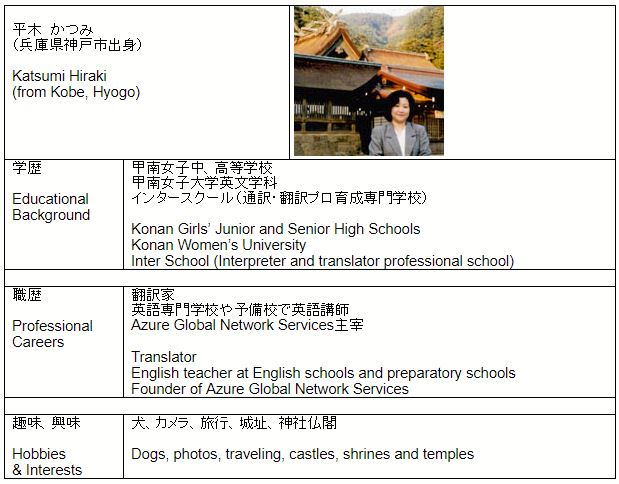

まねきねこ

日本の商店や飲食店の入り口に猫の置物が飾られているのを見たことがありますか。それは日本語で「招き猫」と呼ばれ、商売繁盛をもたらすと言われています。一般的に招き猫は幸運を招き入れるようにどちらかの前脚を挙げています。右脚を挙げている招き猫は商売繁盛、左脚を挙げているものは千客万来にご利益があるとされています。招き猫はたいてい挙げていない方の手で小判を抱えています。招き猫は陶器が最も多いのですが、石、ガラス、布、紙でできているものもあります。また、人形だけでなく絵やタペストリーも人気があります。

Have you ever seen a cat-shaped figure at the entrance of Japanese shops and restaurants? It is called “maneki-neko” in Japanese, and it is said to bring good luck to businesses. (“maneki” means to invite and “neko” means a cat in Japanese). Usually a maneki-neko has either paw raised as it beckons good luck to come in. Raising a right paw is said to bring good luck for money, while raising a left paw is believed to invite many customers. A maneki-neko usually holds a koban (a Japanese gold coin) with the unraised paw. A ceramic maneki-neko is the most common, and you can also find ones made of stone, glass, cloth or paper. As well as figures, paintings and tapestries are also popular.

時には両脚を上げている招き猫もありますが、欲が深すぎると商売が失敗するとしてこれを避ける人もいます。また、両脚を挙げている姿が「お手上げ」を連想させることがあります。もし両脚を挙げる招き猫を求めるならば、片方の脚が低い位置にあるものをお薦めします。

Sometimes you will find a maneki-neko that raises both paws, but some people hesitate to display this style because they believe greed will kill their business. Moreover, the pose of raising both hands sometimes suggests “Ote-age” (literally, “ote” means hands and “age” means to raise), a typical gesture which Japanese people make in case they give up. If you want a maneki-neko which raises both paws, I recommend you buy a maneki-neko which raises one paw a little lower than the other.

招き猫の起源には諸説あります。東京都台東区の浅草寺や浅草神社が招き猫発祥の地だとする説があります。江戸時代に浅草で住んでいた老婆が、生活に困窮して可愛がっていた猫を手放します。老婆はとても悲しく思っていたところ、その猫が夢の中で自分の姿を人形にするように老婆に告げました。そこで老婆は今戸焼(現在の東京の今戸や千葉の船橋で作られていた陶器)で「丸〆猫」(まるしめねこ)と呼ばれる猫の人形を作り、浅草神社の鳥居横で売り始めると人気が出ました。これが現存する招き猫の最古のもので、江戸時代の有名な芸術家の歌川広重の錦絵にも描かれています。

There are some theories about the origin of maneki-neko. In one theory, Senso-ji Temple and Asakusa Shrine in Taito Ward, Tokyo are said to be the birthplace of maneki-neko. In the Edo period, one old woman in Asakusa Town was so poor that she parted with her beloved cat. As the old woman felt very sad, the cat appeared in her dream and told her to make dolls representing itself. Therefore, the old woman made the dolls of a cat called “Maru-shime-neko” from Imado-yaki ware (a type of Japanese pottery from present day Imado, Tokyo and Funabashi, Chiba Prefecture) and sold them next to the torii of Asakusa Shrine. Later the dolls became popular. These are the oldest maneki-neko in existence and were printed on a nishiki-e (a multi-colored woodblock printing) by Utagawa Hiroshige, a famous artist in the Edo period.

東京都世田谷区の豪徳寺で江戸時代に飼われていた猫がその起源だとも云われています。ある日、彦根二代藩主、井伊直孝がにわか雨にあい、豪徳寺の大木の下で雨宿りをしていたところ、1匹の白猫が彼を寺へと招き入れました。城主はとても珍しく、面白ことだと思い寺に立ち寄りました。彼が寺に入った直後にその木に雷が落ちたので、猫のおかげで命拾いができたと思った藩主は大いに猫に感謝をしました。当時、豪徳寺は財政的に困窮し、寂れていたので城主は再建のために寄進をして、井伊家の菩提寺にしました。

Another theory is that Maneki-neko originate from one cat kept in Gotoku-ji Temple in Setagaya Ward, Tokyo, in the Edo period. One day, when the second lord of the Hikone Clan, Ii Naotaka, was taking shelter from the sudden rain under a tall tree in Gotoku-ji Temple, he realized that one white cat was beckoning him into the temple. He thought that it was really unusual and interesting, so he dropped by the temple. Soon after he entered the temple, lightning struck the tree. He was appreciative and thankful to the cat because he thought he had a narrow escape. Since Gotoku-ji Temple was in great financial difficulties and had become desolate at that time, this lord contributed to this temple for its reconstruction and made it the Ii Family’s temple.

この出来事の後、猫型のお守りで有名になりました。ところで、このお寺の縁起物の招き猫は右脚を挙げており、小判を持っていません。その理由は、招き猫は幸運を招くけれど、成功の機会は自分自身で掴まなければいけないと考えられるからです。

After this event, Gotoku-ji Temple became famous for cat-shaped talismans. Incidentally, the maneki-neko of this temple doesn’t have gold coins. The reason is that the maneki-neko can bring in good luck, but the owners of the maneki-neko should seize their own opportunities for success.

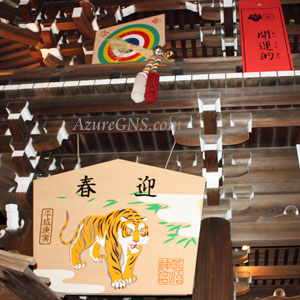

数年前、家族で豪徳寺に行きました。願いが叶って奉納された可愛い招き猫が並んでいる姿に思わず微笑みました。境内の2006年(平成18年)に落成した三重の塔にいくつかの猫の彫刻が彫られていました。一層部分に十二支の彫刻があります。日本の十二支には猫はいませんが、ここでは鼠に挟まれて右脚を挙げている白猫がいました。猫の右側の猫は小判をくわえていました。

Several years ago, I went to Gotoku-ji Temple with my family. We naturally smiled to see many cute maneki-neko which were offered to the temple after the fulfillment of wishes. We saw some cat sculptures on the three-story pagoda which was built in 2006 (Heisei 18th yr). On the first story, there were sculptures of Junishi (the twelve animal signs of the Oriental Zodiac) and among them we saw a white cat who raised its right paw and was accompanied by two rats, one on either side, although a cat was not a member of Junishi in Japan. The rats on the right side of the cat had a gold coin in its mouth.

二層部分には仏像の彫刻の下に白い招き猫がいて、その左には2匹の猫が寝そべった彫刻がありました。同じく二層部分の異なる面には珠で遊ぶ猫もいました。境内を散歩中の近所の方がこれらの猫のことを教えて下さいました。カメラの望遠レンズを持って行かなかったので鮮明な写真を撮れなかったのは残念でした。その他いたるところにあらゆる猫の姿があり、このお寺は猫好きさんの聖地にもなっています。

On the second story, there was a white maneki-neko below the statue of Buddha, and two sculptures of cats were lying on the cat’s left. Another sculpture of a cat was playing with a ball on another side of the same story. A neighbor taking a walk in the precinct showed those sculptures to us. We could not unfortunately take good photos of them because we didn’t bring a telephoto lens for our camera at that time. We saw other various figures of cats in the temple which is a sacred ground for cat-lovers.

滋賀県彦根市の有名なマスコットキャラクターのひこにゃんはこの豪徳寺の白猫がモデルになっているので、寺内にはひこにゃんの姿もありました。もしあなたがひこにゃんに興味をもったなら、彦根城に行くこともお薦めします。運が良ければ本物のひこにゃんに遭遇するでしょう。

Hikonyan, a famous mascot character in Hikone City, Shiga Prefecture, is modeled on the white cat in Gotoku-ji Temple, so you see some figures and pictures of Hikonyan there. If you become interested in Hikonyan, I also recommend going to Hikone Castle. If you are lucky enough, you might see the real one.

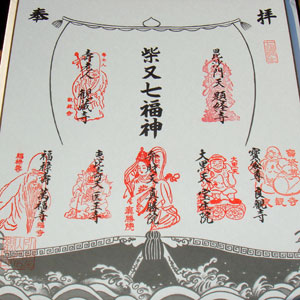

東京都台東区にある今戸神社は招き猫発祥の地と謳っています。この神社は縁結びの御利益がある神社としても有名で、絵馬もペアの招き猫でした。(絵馬は絵が描かれている小さい木の板です。元は馬の絵が描かれています。 願い事と名前と住所を書き、神社や寺に奉納します。) 私の頂いたおみくじも招き猫がついていました。

In addition, Imado Shrine in Taito Ward, Tokyo also introduces itself as the birthplace of the maneki-neko. This shrine is also famous for answering prayers for matchmaking, so couples of maneki-neko are on the ema (An ema is a small wooden board with a picture, originally a picture of a house on it, on which one writes his or her prayer or wish, name and address on the ema and offers it to a shrine or a temple). The omikuji (a written oracle) I received included a maneki-neko.

下町風情が残る東京都台東区の谷中には、招き猫好きが泣いて喜ぶようなお店があります。その名は谷中堂、オリジナルの招き猫が所狭しと並んでいます。定番の招き猫から、個性的なものやオーダーメイドのものまで購入することができます。素焼きの招き猫にペンで彩色する絵付け体験や、かわいい猫のスイーツを楽しむこともできます。

Yanaka area in Taito Ward, Tokyo still has the atmosphere of an old town. A shop named Yanaka-do, which might make maneki-neko lovers cry with happiness, was in the area. The shop is full of various original maneki-neko: standard ones, unique ones and custom-made ones. You can also enjoy painting an unglazed porcelain maneki-neko with pens and eating cute cat-shaped sweets.

招き猫は日本だけでなく海外でも有名です。たとえば、台湾や中国でもたくさんの招き猫を見かけます、そして欧米でも「welcome cat」(歓迎する猫)とか「lucky cat」(幸運の猫)として知られています。もしあなたが商売に成功したいと思ったり、運が悪いと感じたりしたら、招き猫を手に入れて、お宅の玄関に飾ってみませんか。

Maneki-neko are popular not only in Japan but also in other countries. For example, we can see many maneki-neko in Taiwan and China, and they are also known as “welcome cat” or “lucky cat” in the West. If you want success in your business or you feel unlucky, why not get a maneki-neko and display it in the entrance of your house?