伏見稲荷大社と日本人の宗教観

「神を信じていますか?」それは一緒に伏見稲荷大社を訪れた友人の友人であるロシア人が着いて直ぐ私に尋ねた質問でした。彼は日本で宗教的な場所を訪れて純粋に日本人の宗教観を知りたかったのだと思いますが、日本ではこういった質問をされることはまず無いので、私は面食らい即答することができませんでした。私は信仰心の熱い人間ではありませんが、神社やお寺を訪れた際には健康や幸せを願って手を合わせます。海外の方の中には日本人は宗教心が薄いと言われる方もいます。確かに日常生活の中で宗教の集まりに通っているとか毎日お祈りをするといった宗教の存在を感じる機会は余りありません。

“Do you believe in God?” This was the question that my friend’s friend from Russia asked me as soon as we arrived at Fushimi Inari Taisha. I think he simply wanted to know the Japanese perspective on religion at the time when he was visiting a religious place in Japan, but I was overwhelmed by his question and couldn’t immediately answer since it is uncommon to be asked such a question in Japan. I am not a religious person, but I pray for good health and happiness whenever I visit shrines and temples. Some people in other countries say that Japanese people are not religious. It is true that in our daily lives we rarely have occasions to see other people’s religious practices like regularly attending religious gatherings or praying daily to God.

ではなぜ沢山の日本人が寺社仏閣を訪れるのでしょうか?有名な建物や美しい庭や歴史的な所蔵品を見るという観光目的の方は確かに多いと思います。しかし、観光目的なのでお参りはしませんという人はまずいません。訪れた人はたいていご利益を求めて手を合わせます。お正月には非常に多くの日本人が初詣をします。ほとんどの神社には複数の神様が祀られています。日本の古来からの宗教、そして今も国の宗教とされてるのは神道です。八百万の神々と言われる様に自然のもの全てに神が宿ると考える多神教であり、沢山の神々を敬うこの姿勢が日本人の信仰心が薄いともとられるおおらかな宗教観に繋がっているのかもしれません。そして物を大切にしたり、自分の家だけでなく公共の場もきれいにしておこうという姿勢にも表れているのかもしれません。

Then, why do many Japanese people visit temples and shrines? I am sure that one purpose for most is sightseeing to see famous architecture, beautiful gardens and historical artifacts. However, it is very rare that visitors don’t pray even if their purpose is sightseeing. People usually pray for good luck. During the first three days of the New Year, an enormous number of people visit shrines or temples to make a wish for the New Year. Most shrines have several deities. The religion which has existed from ancient times in Japan and is still considered the national religion is Shinto. As it is said that there are myriads of deities in Shinto, it has polytheistic as well as animistic beliefs. An attitude which worships many deities leads to a generous perspective of religions, which is sometimes regarded as an irreligious attitude. This animistic belief may also make people carefully use things for a long time and keep not only their own houses but also public places clean.

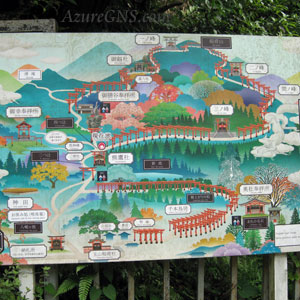

初めて伏見稲荷大社を訪れた日は小雨が降っていて、千本鳥居の奥は薄暗く見えました。しかし雨が止んだ後にもやの中に鮮やかな朱塗りの鳥居が立ち並ぶ光景はとても幻想的で、崇高な存在がずっと奥に潜んでいるかの様な神秘的な雰囲気でした。鳥居は人間の世界と神の世界を分ける門の役割をしているとされています。本殿は山の裾にあるのですが、そこから頂上まで非常に沢山の鳥居が並び、山を登りながら多くの神々に参ることができます。通常神社ではお賽銭をあげてお参りをしますが、伏見稲荷大社ではお賽銭だけではなくそれぞれの祠に複数のサイズの小さな鳥居が沢山供えられており、他の神社には無い独特な光景を見ることができます。

When I visited Fushimi Inari Taisha for the first time, I couldn’t see all the way to the end of Senbon Torii because of the misty rain. However, the scenery of so many bright red orange Torii in the fog after rain was very mysterious and I felt a sacred atmosphere as if powerful spirits dwelled in the deepest place of the mountain. Torii is defined as a gate which separates our world and the deities’ world. The main building is located on the foot of the mountain and from there to the top there are many Torii. You can pray to many deities as you climb the mountain. We usually offer money when we pray to deities, but at some small shrines of Fushimi Inari Taisha as well as offering when we pray, we can also pay for several sizes of wooden Torii, this is not seen at other shrines in Japan.

山を登る参道の途中には社務所やお茶屋があり、お守り・飲み物・食べ物等を買うことができます。どの建物も古い作りですので、趣があります。山を登ってきた足を休め、周りの景色を眺めることで、非日常的な雰囲気に浸り、気持ちを落ち着かせることができます。他の宗教でもそうだと思いますが、神に祈ることは自分が日常生活で叶えたいと思っている願いや夢を意識する良い機会であり、これから自分の願いがかなうかもしれないという希望を持つことによって来る前より前向きな気持ちになって帰ることができますが、山という広大な敷地にある伏見稲荷大社は頂上までで登ると往復2時間ほどの道のりで、山を登ったという達成感も味わうことができます。

There are shrine offices and small shops on the mountain path where you can buy amulets, drinks, food and so on. Every building is old and has an otherworldly atmosphere. In front of the shops you can rest your legs that have become weary by climbing the mountain, separate yourself from ordinary life by looking at the scenery and calming your mind. I think every religion has this benefit but making a prayer to deities is a good opportunity to realize your wish and dream that you have in your daily life. You can also be more positive when you go home from the hope of your wish coming true. Besides, it takes around two hours to climb up and down the mountain and you can also feel a sense of accomplishment for scaling the mountain.

海外では宗教の話はタブーだと聞いたことがあります。それは宗教の違いで言い争いになることを避けるためです。ただ日本人が余り宗教について話をしないのは、当たり前の様に神々が日常生活に溶け込んでいるからかもしれません。ご先祖を祀るための仏壇がある家は多いですし、火の神である荒神様を台所に祀っておられる方もいらっしゃると思います。町々には神社やお寺が必ずありますし、道沿いに小さな社を見かけることもよくあります。トイレの神様という歌が流行ったのを覚えている方もいらっしゃると思いますが、神道では厠の神も存在するのです。

I hear that talking about religion is sometimes taboo in foreign countries. This is to avoid arguments between people of different religious beliefs. However, in Japan talking about religion not so often might come from the regular existence of deities in our daily lives. I think many houses have a Buddhist altar for their families and some houses also have an altar for the fire deity in their kitchen. You can see at least one shrine and temple even in a small town where you visit. Small shrines can be often seen on the roadside. Some of you probably remember the song named “the lavatory deity.” Shinto even has a deity for the lavatory.

宗教は信じる人の考えを形作るものであり、人を律したり良い行いをしようと意識させることに役立っている反面、宗教によって考え方が異なる場合があるため、それが争いを引き起こしてきたのも人類の歴史を見ると明らかです。特に一神教は他の神を認めません。絶対的なものを信じるあまりに考えに寛容さが無くなってしまったり、起源が同じとされている宗教でも宗派の違いで争いがあります。

Religion creates the thinking of people who believe in it. It also helps to restrain people from bad behavior and encourages them to do good things. On the other hand, in human history it is obvious that religion has also caused fighting due to the different beliefs between religions, especially monotheism which doesn’t accept other gods. Some people believe in one absolute God too strongly and close their minds to other beliefs. There are also conflicts between religions which are said to have the same origin.

私がオーストラリアにいた頃、クラスメイトのトルコ人の女性と観光目的で教会へ行きました。ホストマザーにその話をしたところ、イスラム教の人が教会に行くなんてととても驚いていました。(クラスメイトはイスラム教ではなかったのですが、トルコでは国民の大部分がイスラム教徒です。) ただ、観光目的であろうと他の宗教の建物なり敷地なりを訪れることは良いことだと思います。なぜなら訪れることにより、その宗教を知ることができるからです。知ることは理解することへの第一歩です。2020年のオリンピック・パラリンピックを前に、今日本には沢山の外国人が訪れています。伏見稲荷大社でも多くの外国人を見かけました。もっと多くの外国人が伏見稲荷大社を訪れ、そこに沢山の神々が一緒に祀られることを知って欲しいと思います。そうすれば、他の宗教への理解が生まれるきっかけになり、本来人を幸せにするべき宗教で争うことを止められるのではないかと感じました。

When I was in Australia, I went to a Christian church with my Turkish classmate for sightseeing. I told this story to my host mother. She was so surprised and said, “I can’t believe a Muslim girl went to a Christian church!”(My classmate wasn’t a Muslim, but most Turkish people are.) Yet, I think visiting other religions’ facilities and places is a good thing. Because you can have an opportunity to learn about that religion. Knowing something is the first step to understanding it. Before the 2020 Olympics and Paralympics many foreigners will visit Japan. I also saw crowds of foreigners in Fushimi Inari Taisha. I hope that more foreigners visit Fushimi Inari Taisha so that they can learn about the many deities enshrined together. I believe it will be a good opportunity for them to understand other beliefs and resolve conflicts between religions, which are supposed to make people happy.