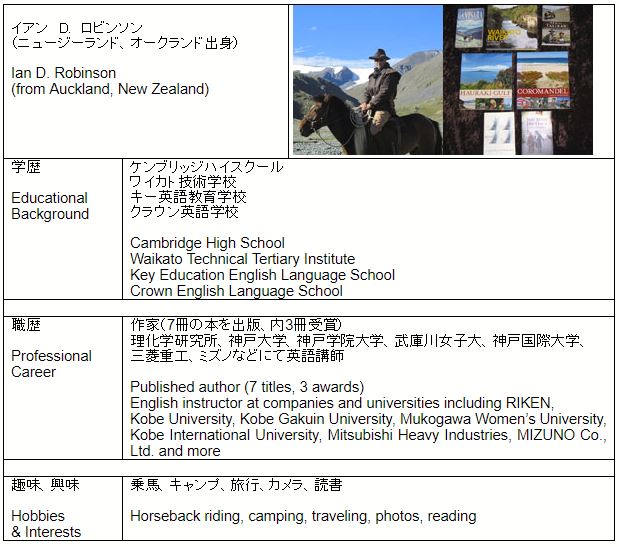

モンゴル単独馬上横断

As a child I had always been fascinated by stories I’d read about the explorers of old. Those brave souls who had ventured into unknown wildernesses inhabited by wild animals and even wilder people. Places where, on one hand cities of gold and untold riches could be found, but on the other swirling oceans, man-eating tigers and monsters waited. With those adventure books tucked under my pillow at night, I would dream of someday making my own incredible journey.

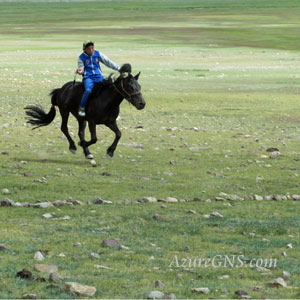

In 1992 the vast and largely forgotten nation of Outer Mongolia finally threw off the shadows of Soviet guided communism and opened itself to the world. In London I was one of the first people to be issued a tourist visa for individual travel. My goal was to spend as long as I could in the country, to see into the lives of the Mongolian nomads, the descendants of Genghis Khan’s warrior hordes, and most importantly to travel as they did and always had-on Mongolian horses.

With the help of a local family, I bought my first horse and set off from near the capital city of Ulaan Bataar and headed west. Ahead of me lay the adventure I had dreamt of as a child, I would meet tribes who had, apart from Russians, never met outsiders. I would meet people who had never, and probably would never, see the ocean. I would ride into valleys where most likely a westerner had never been. I wouldn’t find riches, but I would see sunsets of gold in the desert and would find friendship and hospitality from strangers who lived their entire lives in round tents.

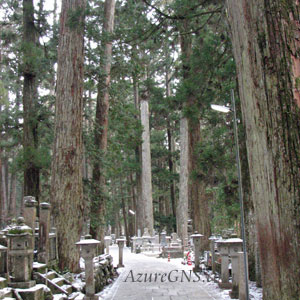

After a month of riding, I had crossed the vast grasslands of Eastern Mongolia and entered the forested mountains of the Hangay Nuruu in the center of the country. The rugged terrain, thick forests and remoteness of the mountains would test me, and one terrifying day would push me to my limits.

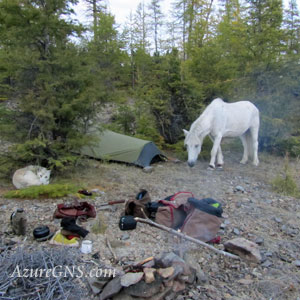

It was a long valley and an even longer day. I climbed higher and higher into the mountains but somehow, I lost the trail. By evening I realized I had gone the wrong way as I found myself in a dead end in the valley surrounded by sheer rock peaks; there was no way out. I lead my horse back down a short distance and found a place to camp just as darkness started to fall. It was a high camp and a freezing night.

I woke to a sunny, clear morning but as I packed my tent and saddled my shivering horse, clouds crept over the peaks around me. Rain began to fall not long after we set off down the valley and within a short time the rain turned into snow. It was a worrying sign and I could feel the tension inside me beginning to assert itself. At the altitude I was in and in such remote mountains, there was very little margin for error, and I had already made one mistake.

While wind blew up the valley driving the snow into my face, my poor horse tried to turn his head to avoid the blizzard, but I pushed him on. Three hours later I reached the point at which I should have turned off the day before. Here I had to make a choice: to head on and try to cross the range in the worsening weather, or head back the way I had come to find the nomad camps I had passed the day before. Turning back was the sensible thing to do. I could find safety and it was all downhill over land I had already ridden. However, I also knew it was a very long way back to the camps. I’d be lucky to get there by nightfall, but by riding on across the range I might find other camps closer. It was a dangerous gamble, but I decided to take it.

We struggled on. The ground was soft and boggy and very difficult going for my poor horse. I often lost the trail, but we’d stumble on until we found it again. The layer of tension inside me was now converting itself to fear and was creeping closer to the surface as I got colder, wetter and higher in the valley. My horse stumbled again.

“Come on! Go!”

I tried to stay calm knowing that panic would kill me quicker than the cold but fearful thoughts found their way in. Was I pushing my luck too far trying to cross a pass in this weather? What about hypothermia? How long did it take to set in? How cold could you get before it was too cold? Was I too cold already? Every few minutes I would start to shiver uncontrollably.

Snow was piling on my hat and saddlebags and my horse’s neck was a frosty strip of white. At the same time, I was becoming more and more anxious. I wasn’t in immediate danger as long as nothing went wrong, as long as we didn’t lose the trail completely, as long as the weather didn’t get any worse, or as long as my horse kept going. He was struggling over the rough, wet ground but every time he faltered, I would shout at him to keep going. I was trying to take the fear and stress I felt out on him. I should have had more faith in my brave little Mongol pony; he carried me all the way to the top.

Finally, there we stopped next to a pile of stones built to mark the pass. I climbed out of the saddle and tried to tie a bandana around my face to keep warm, but my fingers were so numb I couldn’t do it. I gave up and set off on foot leading my horse behind me down into the next valley. Snow was blowing in swirls around us and visibility was reduced to just a few meters.

An hour later we had made it to the valley floor. The snow turned back to rain but at least the trail was easier. I got back on my horse and rode on with ice-block feet trying to see ahead and ever hopeful that I would spot the welcome sight of the round Mongolian tent, or ger, in the distance that would mark shelter, warmth and safety.

At about six o’clock in the evening I almost stopped and set up camp. I just wanted to get into my sleeping bag and fall asleep, but all my clothes were wet, and I had nothing else to change into. I needed to build a fire, but with nothing dry to put on, I might not be able to warm up and I knew that could be fatal.

I rode on scanning the way ahead through the clouds looking for any sign of people. I was still high in the valley, too high perhaps for there to be any nomads camp, and then again there might not have been anyone living in the area at all. Then in the far distance I noticed something on a hillside, something white. Were they rocks? Patches of snow? They were moving, sheep! I’d never been so pleased to see some in my life. I felt they were a sign of safety, that people wouldn’t be far away, and I was going to make it.

At about eight o’clock I found a camp of a single ger, just a woman and her two small children. “Sain-bai-nu.” I greeted her with the usual Mongolian phrase, are you good? “Sain-bai-nu.” She replied.

“Bi huting bain.” I told her, I’m cold.

“Aa.” She nodded and motioned for me to enter the ger.

I stepped inside and sat by the stove, the fire not exactly blazing but it was better than nothing. The woman made me some tea, poured me a bowl and then took her children outside. I sat there cradling the warm tea bowl in my freezing hands, breathing deeply and fighting the urge to lie down and go to sleep. Half an hour later, the woman still hadn’t returned so I opened the door and looked outside. She was nowhere to be seen and a horse which had been tethered near the ger was gone too.

Just then I looked down the valley and saw an old truck heading towards the camp. It stopped a few hundred meters and six men jumped from the back of the vehicle and stood watching me. They were all armed with rifles and I wondered if they were a hunting party heading off into the hills. We stood watching each other for several minutes until the men started waving at me to come towards them. I stayed put as I was exhausted and the effort of trying to communicate with a group of people was too much to handle. Eventually they walked towards me but stopped several meters away. One of the gun totters stepped forward.

“Henbe?” he shouted at me. Who are you?

“Bi juulchin.” I’m a tourist, I told him and I pointed towards the pass and indicated that I had just come over it. All at once the men started shouting questions at me at a speed that was impossible to understand. I held my hands up for them to stop and told them in Mongolian about the woman and the children that had been at the ger.

“Mini ger bain!” the man with the gun told me, they’re at my ger, and he pointed further down the valley to where his camp must have been.

I suddenly realized what had happened. The woman had become frightened at the sudden arrival of the stranger and had run off to get the menfolk to help. I also realized that the rifles the men had brought were meant for me. It had been a tough day; first hypothermia, and then I was in danger of being shot!

The tension of the situation broke. I apologized to the men and explained who I was and what I was doing. We all went inside the ger and had tea.

“Bi huting bain,” I repeated to the man.

“Aa, oonirda huting bain.” He agreed that it was a cold day, though it was probably nothing to him. After tea we set off on foot to the main camp a short distance down the valley, after everyone had pumped the cartridges out of their rifles, even though they weren’t taking any chances with this stranger.

The whole village turned out to see that they had brought me in alive. I was taken to one ger and served more hot tea and a large bowl of fatty mutton lumps and homemade noodles. The food poured energy into my cold, tired body and I could feel it flow through me as if I had been injected with a powerful drug. I was so glad I had carried on and not camped higher in the valley as I had wanted to earlier. However, exhaustion came upon me like a wave and I was utterly helpless to stop it.

“Bi ontno herecti.” I need to sleep, I told the man, and he showed me to a bed at the back of the ger that was to be mine for the night. I unrolled my sleeping bag and peeled off most of my wet clothes in front of the tent full of people watching me. I was beyond caring, I crawled into the warm bag, pulled the hood over my head and was lost to the world.

I spent three days resting and recovering, both for myself and my horse, before heading on west. Over the next couple of months, I would leave the Hangay Nuruu Mountains and head out onto the empty plains of Zavkhan before reaching the mighty Altai Mountains in Mongolia’s far west. Here I would encounter weather and conditions as bad, if not worse than those I went through that freezing day, but by then I’d be better equipped, more experienced and more able to deal with the challenge. By the time the fierce Mongolian winter began, I would have travelled nearly 3000 kilometers over four months. The child dreaming with a book under his pillow had found his own adventure.